“The most enlightened preservationists are trying to restore more than buildings. They wish to restore a sense of community and of humane and civilized values in an age of bigness and speed and, too often, of loneliness, fear and conflict.” –Mills Lane

Source: Heather L. Young (flyoungstudio.wordpress.com)

I’ve just returned from the state of Georgia where I was astounded by the city of Savannah. The “Hostess City of the South” offers some important lessons for how struggling cities can make themselves more livable for their inhabitants…

In 1733 James Oglethorpe founded Savannah as a refuge for those who had become insolvent during England’s flurry of 18th century urbanization. Oglethorpe set out to create a self-sufficient agrarian economy in which slavery, lawyers, Catholics, and hard liquor were forbidden. Over time the prohibitions were eliminated but Oglethorpe’s vision of social equity and civic virtue live on in Savannah today.

Savannah has experienced its share of ups and downs, especially in the years after the American Civil War. By the middle of the 20th century the city faced the same troubles many cities faced at that time, and plenty others that were prevalent in the American South. During the down-years the city’s beautiful townhouses and public lands fell victim to neglect:

A half century of economic decline and the impact of the automobile in the first part of the 20th century resulted in a city’s heritage wallowing in sad decay. By the mid-1950s, the loss of the Wetter House, beloved City Market and demolition threats to the Isaiah Davenport House sparked the formation of Historic Savannah Foundation. Led by seven visionary women, HSF purchased the c. 1820 Davenport House and thus began the organization’s formal entry into the world of preservation and real estate. (myhsf.org)

As a broader, diversified economy was established, the city used its unique strengths – its architecture, history, public spaces – to rebuild without getting bogged down by the weaknesses of its past. How did Savannah (pop. 142,000) become such a great city over the last 60 years? Public spaces, the arts, and the rehabilitation of derelict buildings have played an important role…

Public Spaces

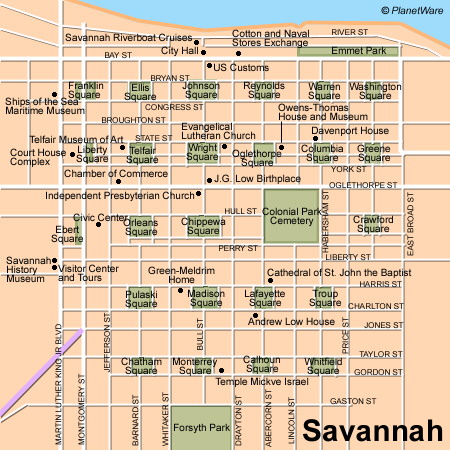

Source: planetware.com

The abundance of public spaces in Savannah contributes greatly to the city’s unique environment. Oglethorpe’s plan for the city involved a series of wards, each comprised of eight blocks and a public square. The four large blocks north of each square were to be used for residential purposes, while the four smaller blocks (two east and two west of each square) would serve as the sites of civic and commercial structures. That tradition continues today, making Savannah a vibrant, socially-engaged city. Walking through Savannah is an unforgettable experience. There is a public square every two blocks – 24 in the historic old town, and more in the newer neighbourhoods. Each square has abundant seating under a canopy of live oak trees and Spanish moss, and most have a fountain in the centre or some sort of monument to the city’s past. I found that sitting in a Savannah square for any length of time often resulted in a conversation with a local who was passing by. Urbanist John Massengale called Savannah’s layout “the most intelligent grid in America, perhaps the world.”

Each square has its own personality and fascinating history. The famous bench scenes from the movie Forrest Gump were shot in Chippewa Square, named after America’s decisive victory in Niagara during the War of 1812. In Forsyth Park, an abandoned World War I training fort was transformed into a cafe and public washrooms in 2010. The huge Confederate Monument in the park was made in Nova Scotia and transported to Savannah by ship so that it would never touch “Yankee” soil. Lafayette Square, named for the French hero of the American Revolution, is the centre of the city’s St. Patrick’s Day festivities. These squares contain the very stories that unite the community and are integral to Savannah’s identity.

The Arts

The Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) opened its doors in 1979 with 7 faculty members and 71 students. Today, over 10,000 students are enrolled in the college, and campuses have been opened in Atlanta, Hong Kong, and Lacoste, France. What started with 4 people, a $200,000 loan, and one building has blossomed into America’s 2nd largest private art college. The civic-minded college has collaborated to organize annual events such as the Sidewalk Arts Festival, Savannah Film Festival, SCAD Style, deFine Art Festival, Art Educators’ Forum, and Rising Star. The college also runs the Gryphon Tea Room in an old Scottish Rite Masonic Temple. In its 35 years, SCAD has restored or renovated 67 old and often derelict buildings throughout Savannah:

The Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) opened its doors in 1979 with 7 faculty members and 71 students. Today, over 10,000 students are enrolled in the college, and campuses have been opened in Atlanta, Hong Kong, and Lacoste, France. What started with 4 people, a $200,000 loan, and one building has blossomed into America’s 2nd largest private art college. The civic-minded college has collaborated to organize annual events such as the Sidewalk Arts Festival, Savannah Film Festival, SCAD Style, deFine Art Festival, Art Educators’ Forum, and Rising Star. The college also runs the Gryphon Tea Room in an old Scottish Rite Masonic Temple. In its 35 years, SCAD has restored or renovated 67 old and often derelict buildings throughout Savannah:

SCAD has made the city its campus and many of its classrooms, offices, galleries, athletic facilities and student housing adjoin squares. The many and varied activities of its students, faculty and staff add greatly to the life of the Squares. (pps.org)

SCAD has created and supported a rich arts community in the city. Leafing through Connect Savannah, the city’s free weekly magazine, it is obvious the city’s arts scene is thriving. Students can be found throughout the city sketching, painting, building, filming, and contributing to the vibrant life here.

Rehabilitation of Derelict Buildings

SCAD isn’t the only institution that has contributed to the rehabilitation of buildings that have exhausted their original functions. When those 7 visionary women rescued Davenport House from dilapidation in 1955 (the catalyst for the creation of the Historic Savannah Foundation), Savannah’s long and inspiring history of fixing up neglected buildings had begun.

For example, the NAACP worked with the Historic Savannah Foundation to rescue King-Tisdell cottage from demolition, converting the house into Savannah’s museum of African-American history. The former passenger terminal for the Central Railroad was converted into visitor’s centre, history museum, and theatre. The old railroad roundhouse now features a large collection of historic locomotives and rolling stock.

In the 1970s, during the tenure of mayor John Rousakis, the city of Savannah converted its river-front from a derelict collection of rotting cotton warehouses into a pedestrian-friendly area full of cafes, shops, and public spaces. The redevelopment has been referred to by some as “the finest reclamation and restoration of a true antebellum shipping port in the United States.”

Celebrity chef Paula Deen played a role in her home town’s revitalization in 1996 when she purchased the old Sears & Roebuck building, renovated it, and opened up The Lady and Sons Restaurant. In 2001, Deen fixed up the old White Hardware building and opened a restaurant there. The city is full of many other examples of successful restoration projects and local businesses that have enjoyed the benefits of rejuvenated neighbourhoods.

Each city must look at what it values when attempting to build itself into something great. To do this, municipal governments, civic-minded people, businesses, and educational (and other) institutions need to work together. Using the city’s architecture, history, public spaces, and the arts, Savannah has done this well. That’s not a bad model, regardless of what city you’re trying to rebuild.

Articles like this are good to show civic rehabilitations are possible and are indeed happening all over to varying degrees. I think Welland and Niagara in general are going to be not just retirement destinations but places where big city retirees etc also bring cash to start businesses. All this happens slowly and piece by piece and will not be the result of local money and initiatives.

[…] my recent trip to Savannah, Georgia, I wrote about the important role the Savannah College of Art & Design (SCAD) has played in the d… of 142,000. Since the college was established in 1979 with a $200,000 loan and a run-down […]